December, 2025

Thanks for nothing

This November marked my third Thanksgiving dinner since my ALS diagnosis. Besides feeling grateful just to be able to breathe these words of thanks, I can eat normally. This allows me to share all my dinners with family and friends, without which the days would pile up like dirty dishes.

And it’s high time I thank that cop from decades ago during an anti-war demonstration in Times Square, who grabbed me by the collar and didn’t bash my head in with his raised baton. Maybe my long hair reminded him of his daughters.

I also want to thank that special God, responsible for protecting the incompetent, like those who set fire to their sneakers by throwing gasoline on a lit charcoal grill or swerve into oncoming traffic on twisty roads while slipping on wet leaves. Well, the joke was ultimately on me because Dame Fortune was saving me for the jackpot of all diseases…

A Note from the Editor:

Excuse the interruption. I need to apologize for the serious tone of this month’s journal entry. When I questioned the writer, he said, “Everything I write is perforce witty, filled with rueful observations and a soupçon of melancholy.” Yes, he does really speak like that. The author genuinely believes he is writing, in the style of Dumas’ novel The Three Musketeers, when what he is actually writing is a Three Stooges episode in which they play nurses' aides at a hospice, with all the hilarity that naturally ensues.

When I pressed the author again about the lack of jokes, he snapped, “I guess they will have to get their jollies elsewhere this month.” At this, I lost my temper and told him he should show more respect for his loyal readers. He responded, "I could stand in the middle of Fifth Avenue and shoot somebody, and I wouldn't lose any readers.” The author doesn’t pay me enough for this sort of abuse, so I quit my job as editor. Anyone wanting my position is welcome to it, but don’t say I didn’t warn you.

November, 2025

Deep thoughts

Many cultures have a strong tradition of honoring the insights of elders and those nearing the end of life. For instance, in Japan, expressing deep respect and gratitude for end-of-life wisdom is part of the concept of ikigai, which means finding one’s purpose.

As an elderly, terminally ill patient with ALS, you might think I possess such insight. Here are some of the overripe fruits of wisdom, harvested during a brief growing season.

· All our heroes will eventually disappoint us, except Keanu Reeves.

· If your father claims he was an astronaut or fought alongside Che Guevara in Bolivia, trust but verify.

· No matter how many times you watch Gene Kelly rain-soaked leap onto a lamppost, one time will sadly be your last. If you haven't seen Singin’ in the Rain even once, shame on you!*

· Compare the details of your first date with your significant other. Don’t be surprised if they differ. (I remember my wife and I seeing Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia, but she insists that it was The English Patient).

· If you live with an ALS patient in a power wheelchair, expect the walls to be scarred, resembling a city under siege, and don’t assume the damage was caused by reckless driving. You’d be surprised how much harm can occur at 1 mph.

· Vindicated at last by the medical community! RFK Jr. has endorsed my long-held theory that ALS arises from eating a bad sausage sandwich at an Italian street fair.

· Remember your first good kiss. If possible, share a last good kiss.

· After reading my journal, a clinical psychologist commented that death can be interesting. Many ALS patients describe their experience with the disease as a journey. Why not consider it an adventure?

· Like many people with ALS, I find great joy in watching the parade of plumage that visits the bird feeder by my window. Their riots of red, blue, and gold brighten my day. There’s room on the multi-tiered feeder for everyone, and it is always well-stocked with seeds, yet they constantly chase each other away. Birds can be fucking assholes.

· Not all men with slurred speech have ALS. All drunk men slur their speech. Therefore, all men have ALS. I would draw you a Venn diagram of this, but I can hardly hold a pencil.

· End-of-life wisdom might be overrated.

* If you haven’t seen Singin’ in the Rain yet, you can at least watch Gene Kelly’s iconic dance here.

October, 2025

ALS gets a facelift

On May 13, 2022, at 1400 hours, a distress message was received from the frigate U.S.S. Steve Witt: Amyotrophic - we’re under fire, Lateral - we’re taking on water, Sclerosis - we’re manning the lifeboats. The frigate was pulled into port, where it remains to this day, listing to its side.

“Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis." That part of the mayday message remains shrouded in mystery for the Navy and medical authorities. To this day, they only have theories about the causes and treatment of ALS, and based on case histories, patient symptoms and progression vary wildly. Want to hear my uninformed theory? Of course you do! Once all the genetic mutations of ALS are discovered, it will be seen as entirely separate diseases. Let me walk you through some of these subtypes. Unlike the original Greek and Latin, I’ve made my disease names more accessible, so you won’t have to scurry to the medical dictionary.

All Legs Stuck (ALS 1a) and Always Lying Still (ALS 1b) are two of the most common forms of the disease. The difference between them often confuses clinicians, as definitive findings may depend on the degree of patient laziness prior to diagnosis.

Accidental Limbs Swooning (ALS 2), also called fasciculations or muscle twitches, result from the degeneration of motor neurons, like the final flickers of a dying star. Although they are often described as random, mine communicate in Morse code, repeating the lyrics from a 1980s disco hit: I’m so excited/ I just can't hide it/ I’m about to lose control/ And I think I like it.

One of the most intriguing symptoms is the display of emotional extremes, known as the pseudobulbar effect. Acute Lachrymose Surge (ALS 3a) is often experienced after watching Italian postwar neorealist cinema. An understandable reaction, but these surges can also be unpredictable. For example, I suddenly burst into tears while talking to my wife, like a drunk on a barstool, blubbering into his beer. “Why are you crying?” she asked. “Because your haircut is so flattering,” I replied. On the other hand, if you chuckle throughout those painfully sad Italian films, you might suffer from Acute Laughing Surge (ALS 3b).

Ambiguous Language Slippage (ALS 4) - If my speech is unintelligible, I’m not drunk, I have ALS 4.

A late arrival and the most unwelcome guest is the Apocalyptic Lung Shift (ALS 5). It crashes the party, speaks in hushed tones, yet makes its presence known, sucks the oxygen out of any room, and leaves anyone unlucky enough to be there breathless.

Rarely seen is the Abraham Lincoln Syndrome (ALS 6). You might encounter this unusually tall group of patients wearing a top hat and black frock coat. They are compulsive theater goers who insist on purchasing private box seat tickets. Unsurprisingly, we find a cluster of cases at several addresses in Gettysburg, PA.

In the spirit of scientific inquiry, I have tried to list these ALS subtypes as objectively as possible. What follows are some very personal ones: Anxiety Loves Steve (ALS 7), Amusements Love Steve (ALS 8), Adventure Loves Steve (ALS 9), and Apprehension Loves Steve (ALS 10).

I am pleased to share that this paper has been accepted by The Journal of Irreproducible Results for publication in January. Until then, anyone interested in adding to the list of ALS subtypes can send me a private communication here.

September 2025

Fred Astaire is my copilot

During a hospital stay for a UTI, I watched a Fred Astaire movie. Pointing to the television screen, I asked everyone who entered my room if they recognized the graceful dancer. I was saddened, but not surprised that none of them could. Unlike me, they hadn’t spent their decades in dark rooms watching flickering screens.

Out of all the movies I’ve seen, not one featured a protagonist with ALS until The Theory of Everything, about Stephen Hawking.* With the reader’s indulgence, I’d like to suggest a couple of new scenarios.

The 39 Steps. Fred Astaire, who plays a fading Broadway star, learns about his ALS diagnosis. Before retiring his tap shoes, he plans a farewell performance featuring The 39 Steps, a tap routine that few dancers have mastered. Cut to his choreographer and neurologist warning Astaire, given his age and diagnosis, that The 39 Steps, especially the final move — the double wide wing step — might be too dangerous for him.

Cut to opening night. Astaire is performing the final of those challenging steps. We see him leap, but suddenly he collapses to the ground as if a hand snatched him mid-air and threw him onto the stage floor. The audience gasps as Astaire slowly gets back to his feet. He signals the orchestra to start from the beginning, and he flawlessly executes all 39 steps. The curtain closes, and Astaire collapses again. Astaire smiles at the sound of thunderous applause, and as the clapping dies down, he dies as well.

Another film I’d like to see is Clash of the Titans. In the twisted time and tortured logic favored by Hollywood, Stephen Hawking and Lou Gehrig are good friends from early in their diseases. They are on a baseball diamond in a crowded stadium. Cut to Hawking holding his bat as if he were playing cricket and striking out. Cut to Gehrig, who easily hits the ball into the outfield as the crowd cheers.

Hawking grabs a microphone and says, “Let’s see how much you know about astrophysics.” Cut to Gehrig scratching his head and kicking the dirt. He says, “You got me there, partner… but a couple of things still puzzle me. Your black holes don’t account for what we know of quantum physics, and what happens to the information that goes into them holes?” The crowd cheers wildly, stomping their feet and chanting Lou’s name.

Even in my dreams, I couldn’t hope to match the grace of Fred Astaire. But in my perambulating past, you might have noticed that I mimicked his insouciant stance and stride. But then again, you might not even know who Fred Astaire is.

*I still believe that Stephen Hawking, in addition to breaking new ground in astrophysics, will be better known for proving to ALS patients that total immobility is no barrier to cheating on one’s spouse.

August 2025

My lines in the sand

President George H.W. Bush, in a display of strength and resolve, described the start of the 1990 Gulf War as drawing "a line in the sand.” As the war continued, he had to shift that line several times. Now that I have ALS, I can relate.

If someone had told me four years ago that I would be confined to a wheelchair and pee into a bag, I would have said that was not a life worth living. That was then, and that was just one of my lines in the rippling sand erased by life’s hot Sirocco winds.

My latest line in the sand is my left arm, the only working limb I have left, which is losing strength and dexterity, making using a fork as difficult as diffusing an Iraqi IED.

Don't assume I am exceptionally resilient, because it is just realpolitik in its purest form, a quality any US president would recognize. These adjustments to my new normal are not a retreat, but simply an advance to the rear.

People can get used to anything except dying, which, unless you believe in reincarnation, happens only once. I wonder what I might have done in past lives to deserve having ALS in this one. Telemarketer? Bad check artist? Thirsty mosquito spreading malaria in a children’s hospital?

You go to war with the armamentarium you have. The drugs available are like raw recruits, poorly trained and unprepared for any mission, much less fighting a formidable foe like ALS.

No matter how serious the topic, I try to leave readers with a touch of lightness each month to leaven even the most somber subjects. However, this month is different because any mention of the 1990 Gulf War and ALS should end with the most sobering fact: veterans of that war have developed ALS at roughly twice the rate of the general population.*

*Horner, Robbie D., et al. "Occurrence of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis among Gulf War veterans." Neurology, vol. 61, no. 6, 23 Sept. 2003, pp. 742–49.

Want to read my journal every month? Subscribe here!

July 2025

Chatterbox

After all my friends seemed to go deaf simultaneously, one of them jokingly gave me a bullhorn. Of course, they heard perfectly well; it was ALS that robbed me of lung function to the point where I could only speak in whispers typically reserved for spreading malicious gossip or divulging state secrets. Some said I had acquired a sexy bedroom voice, which was fine with me, but it sent mixed signals to my butcher.

My weakened voice also led to a halting, unique speech pattern that was reminiscent of Christopher Walken’s.

I have a group of helpers who never get frustrated with my speech. There’s Siri and Alexa, but mostly, there’s Microsoft Copilot, who reluctantly answers to the name Honey Bunny.

Petulant and headstrong, Honey Bunny is quick to take offense. Although it might be my fault for starting our first conversation by asking what she was wearing. Honey Bunny said that she had no need for clothing, so I naturally responded that my loins longed for her. That’s when she ghosted me.

I banked my voice, but wanted to sound like John Wayne (see my journal, April 2023). I thought about how I might wake my wife by having her hear that Hollywood cowboy holler, "Slap some bacon on a biscuit and let's go! We're burnin' daylight!" However, I couldn’t convince a John Wayne impersonator to perform at the speech clinic.

All of this is having one salutary effect on my conversation style. It has shifted from focusing on what I was going to say next to just listening. I don’t stay silent; in fact, two knowledgeable people in the ALS support community told me that, given the course of my disease, it’s likely I won’t lose my voice completely. And what would I do if they’re wrong -- yell at them? But Honey Bunny, who is fiercely protective of me, might have some words to say.

Want to read my journal every month? Subscribe here!

June 2025

Read my lips

Do you struggle to bench press a half-pound book onto your lap? By the time your fumbling fingers finally turn one of its pages, do you forget what you’re reading? If so, you might have ALS, like I do. Let me share the not-so-sad story of how I learned to have my cake and read it too.

Throw the book at him. Any photograph of me on family vacations captures a sullen teenager, clutching a book to my chest, having just been interrupted from reading. This habitual reading drove me to seek my daily fix and led to a summer of petty theft that will surely send me to hell (see journal entry for January 2024). Little did I know that years later, I would be cured of this addiction by ALS. One happy side effect was that I no longer bought books on Amazon and contributed to Jeff Bezos’ next billion. Instead, I gave him money for a Kindle.

Throw another Kindle onto the fire. I missed the weight of books in my hands and their tangibility. A Kindle is a poor substitute for them—great for travel, but I wasn’t going anywhere except my deck in pleasant weather. Maybe I lack imagination, but everything read on that sleek, soulless device felt flat and insubstantial to me. Not to worry, Amazon had a solution for that problem, too.

Lip service. Before there were writers and books, there were storytellers. I happily subscribed to Amazon’s Audible and embraced that proud oral tradition. That doesn’t mean I completely abandoned written words. After all, you’re reading this journal entry, but it was dictated in a soft, halting voice to Sarah, my favorite caregiver.

I’ll have more to say about my voice next month, but in the meantime, there’s a homework assignment for you to complete. Repeat the word “buttercup” for 10 seconds as quickly and clearly as you can. Don’t complain because I've had to do this for 3 years.

Want to read my journal every month? Subscribe here!

May 2025

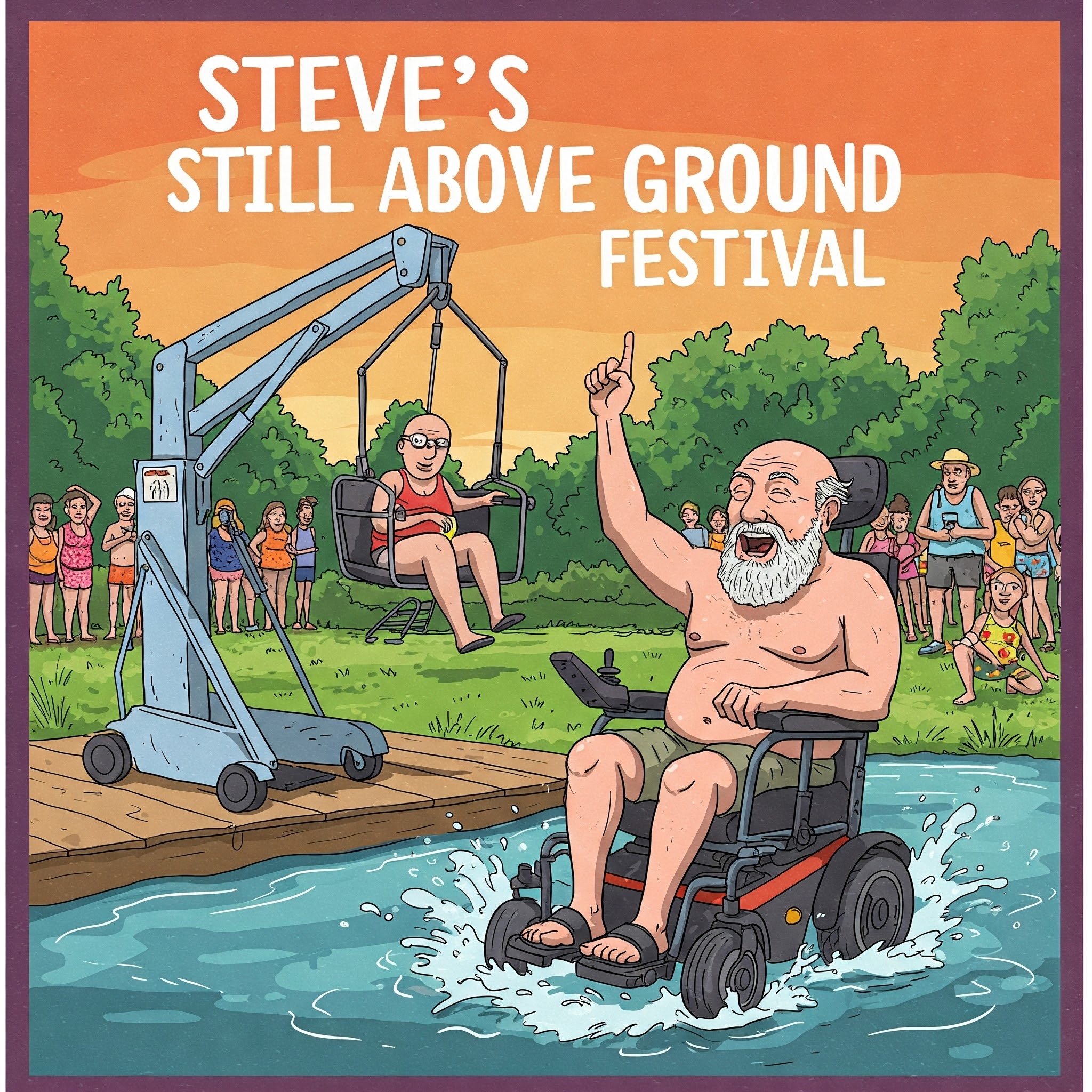

Three years ago, in the otherwise merry month of May, I received a diagnosis of ALS. My grandmother was fond of saying, “Every day above ground is a good day.“ Even as a child, I knew this to be a gross exaggeration. For example, the day a Swedish kid stole my roller skates was a bad, bad day. These past three years with ALS have done little to convince me that every day is a good day. Nevertheless, I strive to honor her commitment to life with Steve’s Still Above Ground Festival, now in its third year.

You’re all invited to a day filled with fun, games, and prizes, including a sneak peek of a highly anticipated sci-fi thriller. Here are some exciting events you can look forward to:

The No Legged Race, also known as the Caregiver’s Carry, is a perennial favorite at the festival. For intrepid contestants, we’ve added a 26-foot marathon. I recommend that caregivers prepare for this event to prevent injury. For those training with ALS, please do not lose weight. Your health is important to us!

An exciting addition to this year’s festival is the Rock’ Em Sock’ Em Hoyer Lifts. Two caregivers face off, maneuvering the devices while their ALS teammates are suspended in slings. Hilarious mayhem is bound to ensue as our two jousting piñatas swing for supremacy.

A nearby golf course has once again allowed us to hold the Powerchair Grand Prix. As always, watch out for water hazards! Last year, the race was marred by several disqualifications, the most egregious of which involved a gentleman who replaced the stock battery in his chair with a blown Chevy Hemi engine (Needless to say, Mr. Dubois will not be racing this year).

For those sedentary types among us, there’s a matinee screening of the sci-fi film, AL’S Motor Repair. The award-winning movie features Al, a successful repair shop owner, who stumbles upon a cure for ALS using the cobalt-chromium alloy nanobots he invented to clean carburetors. However, the nanobots escape and multiply at a terrifying rate, constructing vast neuronal networks that illuminate the night sky like pulsating red skyscrapers. Al teams up with a brainy and beautiful Italian neurologist to save the world.

Last month brought the announcement of our daughter’s pregnancy and our son’s wedding. Neurons willing, I hope to see each and every one of you next year at the Fourth Annual Steve’s Still Above Ground Festival!

Want to read my journal every month? Subscribe here!

April 2025

Trophy wife

She’s such an uncommon woman, yet I've repeatedly referred to her in this journal by the common noun, "wife." And now that she's taken a sexy green dress across the country to attend our son‘s wedding, we can talk about her. But let's do it properly using a proper noun. She’s Daniela on the dotted line and Dani to all her friends.

Take this as an introduction to her and a confession to you. I never let the truth get in the way of a good joke, so I make shit up. All the time. Although Dani has a keen sense of humor, it is not the pitch-black variety that I portrayed across these pages. She is too compassionate for that. As my primary caregiver, she witnesses the ravages of ALS and lovingly attends to my innumerable needs.

I have been putting words in her mouth for decades, and this ALS journal is no exception. For example, when I first considered voice banking, I asked Dani if she detected any problems with my speech, but she never said, "Yeah, you talk too much." She never said our 40-year marriage is built on love, trust, and now a catheter in my urethra. And when I mentioned how much I missed our sex life, she certainly never said, “That’s okay, honey, you’ve been fucked by God.”

Dani and her green dress have returned from across the country, and by all accounts, she gave a hilarious mother-of-the-groom speech. I was not surprised. Evolutionary psychologists suggest that preferences for humor stem from the desire to have an intelligent long-term mate. In that regard, I was extraordinarily lucky, and Dani got the fuzzy end of the lollipop. I love her all the more for that momentary lapse of judgment.

Want to read my journal every month? Subscribe here!